Validation is something we deal with all the time as developers. Probably any of us has added @NotNull, @Min, @Max or such on properties multiple times. But what do you do when the built-in options aren’t enough?

In this blog, I’ll walk you through implementing advanced custom validations in Spring Boot, paired with Hibernate Validator, with practical tips along the way for both beginners and experienced developers.

As always, the code is available in my GitHub repo.

Creating a custom validator in Spring Boot

We’ll use password validation as an example — a classic case where simple constraints fall short. With Passay, a Java library built for enforcing complex password policies, we’ll explore how to implement custom validation effectively while keeping the approach flexible and maintainable.

1️⃣ Add Spring Boot validation and Passay dependencies:

<dependency>

<groupId>org.springframework.boot</groupId>

<artifactId>spring-boot-starter-validation</artifactId>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>org.passay</groupId>

<artifactId>passay</artifactId>

<version>1.6.6</version>

</dependency>

2️⃣ Define a custom annotation with handy **@interface**

@Constraint(validatedBy = PasswordValidator.class)

@Target({ElementType.FIELD})

@Retention(RetentionPolicy.RUNTIME)

public @interface Password {

String message() default "Password is not valid.";

Class<?>[] groups() default {};

Class<? extends Payload>[] payload() default {};

}

3️⃣ Implement the **ConstraintValidator<A, T>**, where **A** is the custom annotation type, and **T** is the type of the validated element

public class PasswordValidator implements ConstraintValidator<Password, String> {

private static final int MIN_COMPLEX_RULES = 2;

private static final int MAX_REPETITIVE_CHARS = 3;

private static final int MIN_SPECIAL_CASE_CHARS = 1;

private static final int MIN_UPPER_CASE_CHARS = 1;

private static final int MIN_LOWER_CASE_CHARS = 1;

private static final int MIN_DIGIT_CASE_CHARS = 1;

@Override

public boolean isValid(String password, ConstraintValidatorContext context) {

List<Rule> passwordRules = new ArrayList<>();

passwordRules.add(new LengthRule(8, 30));

CharacterCharacteristicsRule characterCharacteristicsRule =

new CharacterCharacteristicsRule(MIN_COMPLEX_RULES,

new CharacterRule(EnglishCharacterData.Special, MIN_SPECIAL_CASE_CHARS),

new CharacterRule(EnglishCharacterData.UpperCase, MIN_UPPER_CASE_CHARS),

new CharacterRule(EnglishCharacterData.LowerCase, MIN_LOWER_CASE_CHARS),

new CharacterRule(EnglishCharacterData.Digit, MIN_DIGIT_CASE_CHARS));

passwordRules.add(characterCharacteristicsRule);

passwordRules.add(new RepeatCharacterRegexRule(MAX_REPETITIVE_CHARS));

org.passay.PasswordValidator passwordValidator = new org.passay.PasswordValidator(passwordRules);

PasswordData passwordData = new PasswordData(password);

RuleResult ruleResult = passwordValidator.validate(passwordData);

return ruleResult.isValid();

}

}

4️⃣ Apply the **@Password** validator

public class Registration {

private String username;

@Password

private String password;

}

✅ And done!

More about @Target, @Retention, @Constraint

We could stop here, as the approach already covers many use cases, but true value comes from understanding edge cases and capabilities.

Let’s try to understand the roles of the meta annotations on the **@Password** interface:

@Constraint(validatedBy = PasswordValidator.class)

@Target({ElementType.FIELD})

@Retention(RetentionPolicy.RUNTIME)

public @interface Password {

// rest of the content

}

🔵 @Constraint

The **validatedBy** attribute in **@Constraint** connects a custom annotation to its **ConstraintValidator<A, T>**, where the validation logic lives.

What’s interesting is that it can accept multiple validators, making it flexible for different contexts. Imagine an application where:

- Admins need a 12-character password with uppercase, lowercase, digits, and special characters.

- Regular users only require 8 characters with a digit.

By assigning multiple validators, you can enforce distinct rules within a single constraint, keeping your validation clean and adaptable.

@Constraint(validatedBy = {AdminPasswordValidator.class, UserPasswordValidator.class})

@Target({ElementType.FIELD, ElementType.PARAMETER})

@Retention(RetentionPolicy.RUNTIME)

public @interface ValidPassword {

String message() default "Invalid password";

Class<?>[] groups() default {};

Class<? extends Payload>[] payload() default {};

UserRole role();

}

Validator for admins:

public class AdminPasswordValidator implements ConstraintValidator<ValidPassword, String> {

private UserRole role;

@Override

public void initialize(ValidPassword constraintAnnotation) {

this.role = constraintAnnotation.role();

}

@Override

public boolean isValid(String password, ConstraintValidatorContext context) {

if (role != UserRole.ADMIN) {

return true; // This validator is only for admins

}

return password != null && password.length() >= 12 &&

password.matches(".*[A-Z].*") &&

password.matches(".*[a-z].*") &&

password.matches(".*\\d.*") &&

password.matches(".*[@#$%^&+=!].*");

}

}

Validator for regular users:

public class UserPasswordValidator implements ConstraintValidator<ValidPassword, String> {

private UserRole role;

@Override

public void initialize(ValidPassword constraintAnnotation) {

this.role = constraintAnnotation.role();

}

@Override

public boolean isValid(String password, ConstraintValidatorContext context) {

if (role != UserRole.USER) {

return true; // This validator is only for users

}

return password != null && password.length() >= 8 && password.matches(".*\\d.*");

}

}

🔵 @Target

The **@Target** annotation is used to specify where your custom annotation can be applied in the Java code.

Most frequent possible values include:

**FIELD**— can be applied to fields (instance variables).**METHOD**— can be applied to methods**PARAMETER**— can be applied to method or constructor parameters.**TYPE**— can be applied to classes, interfaces, or enums.

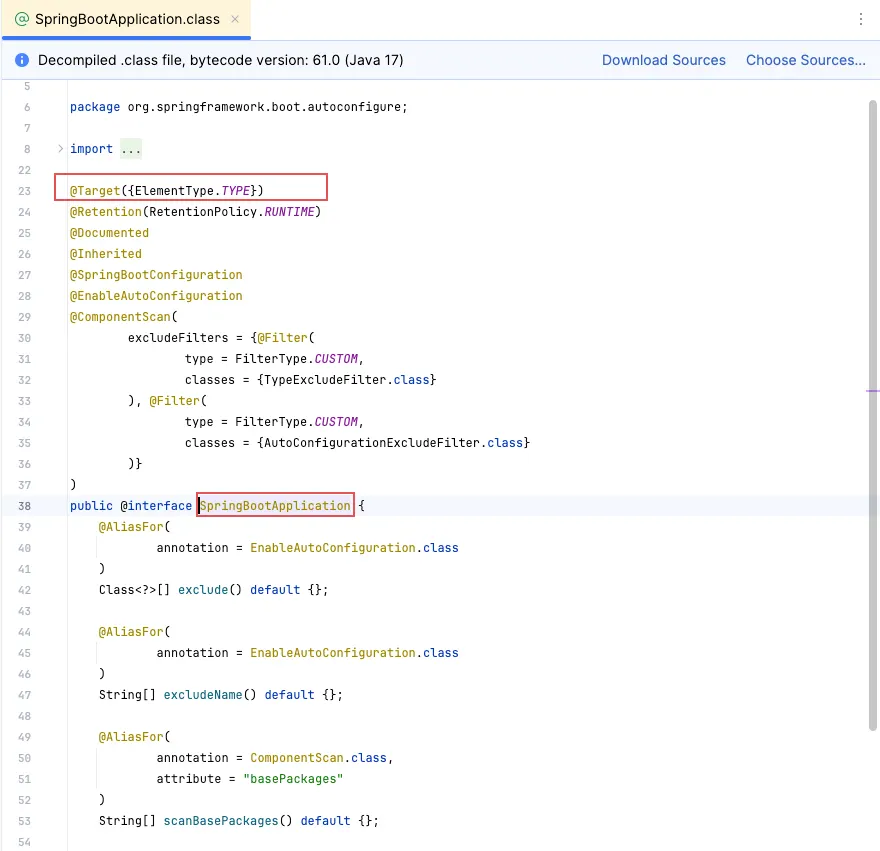

Fun fact: our famous **@SpringBootApplication** is defined as a **TYPE**, combining several annotations under the hood:

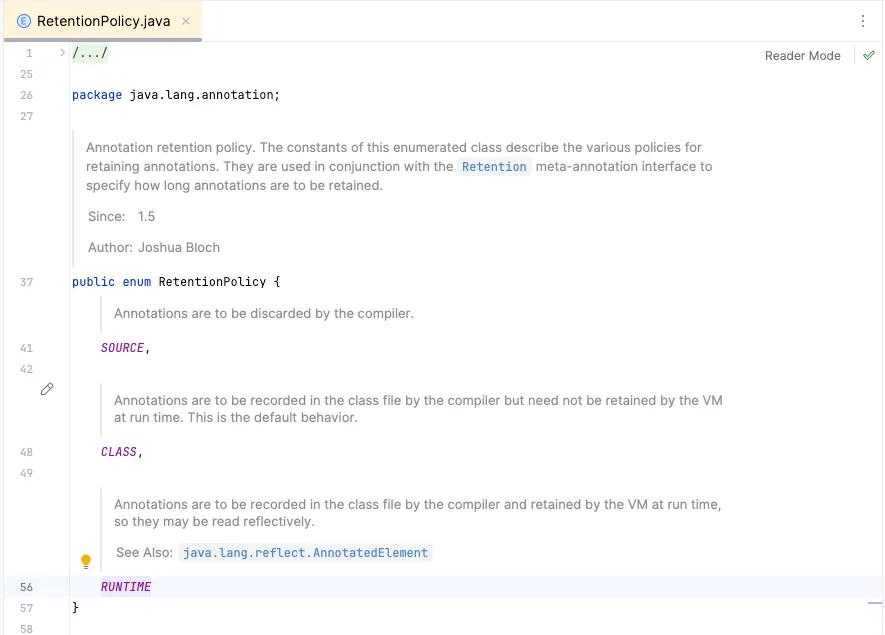

🔵 @Retention

The @Retention annotation specifies how long the annotation should be retained.

Various policies are already well documented in the source code:

• **SOURCE** - Useful for annotations used solely by code-generation tools or IDEs.

• **CLASS** - Useful for bytecode analysis tools but not for runtime validation.

• **RUNTIME** - Required for Bean Validation because the validation framework processes annotations at runtime.

For most of our use cases though, **RUNTIME** would be sufficient.

Understanding message(), groups(), and payload()

The inside of a custom validation annotation interface, like our **@Password**, includes specific attributes that define how the validation behaves:

// Meta annotations

public @interface ValidPassword {

String message() default "Invalid password";

Class<?>[] groups() default {};

Class<? extends Payload>[] payload() default {};

UserRole role();

}

Let’s go over each of these attributes and explain their purpose and see them in action.

🟢 message()

Defines the default error message that will be returned when the constraint fails (default value is empty, if not specified otherwise).

The message can use placeholders (like **{value}**) to include dynamic information about the validation failure.

String message() default "The value '{value}' is invalid.";

More about it in the ‘Fun Facts’ section below.

🟢 groups()

Groups allow us to categorize validation rules and apply them selectively based on context. We could use a single model with group-specific constrains like this:

public interface CreateGroup {}

public interface UpdateGroup {}

public class User {

@NotNull(message = "Username is required.", groups = CreateGroup.class)

@Pattern(regexp = "^[a-zA-Z0-9_]+$", message = "Username must be alphanumeric.", groups = UpdateGroup.class)

private String username;

}

This code would make **username** mandatory under **CreateGroup**, but enforce pattern validation under **UpdateGroup**.

Which one gets applied depends on the group triggered at the controller level (or manually):

@RestController

@RequestMapping("/users")

public class UserController {

@PostMapping

public ResponseEntity<String> createUser(@Validated(CreateGroup.class) @RequestBody User user) {

return ResponseEntity.ok("User created!");

}

@PutMapping

public ResponseEntity<String> updateUser(@Validated(UpdateGroup.class) @RequestBody User user) {

return ResponseEntity.ok("User updated!");

}

}

🟢 payload()

The payload attribute is meant for categorizing or marking constraint violations for special handling. For example, you can define different severity levels for validation failures and process them accordingly.

Defining custom **Payload** classes:

public class CriticalError implements Payload {}

public class Warning implements Payload {}

Retrieve an check the payload in the validator:

public class PasswordValidator implements ConstraintValidator<Password, String> {

private boolean isCritical;

@Override

public void initialize(Password constraintAnnotation) {

isCritical = Arrays.asList(constraintAnnotation.payload()).contains(CriticalError.class);

}

@Override

public boolean isValid(String value, ConstraintValidatorContext context) {

if (StringUtils.isNotEmpty(value)) {

System.out.println(

isCritical

? "Critical validation failure: Password is too short!"

: "Warning: Password is weak."

);

return false;

}

return true;

}

}

🥁 Did You Know These Fun Facts?

🟡 You can programmatically trigger validation using ValidatorFactory

This approach is useful when you need manual validation in service layers, custom workflows, or testing:

ValidatorFactory factory = Validation.buildDefaultValidatorFactory();

Validator validator = factory.getValidator();

public void validateUser(User user) {

Set<ConstraintViolation<User>> violations = validator.validate(user);

if (!violations.isEmpty()) {

throw new ConstraintViolationException(violations);

}

}

🟡 You can get NullPointerException in your custom annotation

Bean Validation does not guarantee the execution order of constraints on a field. This means that even if you have **@NotNull**, your custom validator might still receive a null value if it runs before the null check:

@NonNull

@CustomValidation

private String password;

To prevent **NullPointerException**, explicitly handle null values in your validator:

@Override

public boolean isValid(String password, ConstraintValidatorContext context) {

if (StringUtils.isEmpty(password)) {

return false; // Or return true if you want @NotNull to handle it separately

}

// Custom validation logic here

return value.length() > 5;

}

🟡 You can reference another field from bean during validation

To pass dynamic values to a validator and reference a field in the error message, use a custom annotation with Hibernate Validator’s interpolation, like **int value()** in the following example:

@Documented

@Constraint(validatedBy = MinAgeValidator.class)

@Target({ElementType.FIELD})

@Retention(RetentionPolicy.RUNTIME)

public @interface MinAge {

String message() default "Age must be at least {value}.";

int value();

Class<?>[] groups() default {};

Class<? extends Payload>[] payload() default {};

}

public class User { @MinAge(value = 18, message = “Age must be at least {value}.”) private Integer age; }

### 🟡 You can leverage cross-field validation

Field-level constraints don’t have access to other fields in the object. To compare fields (e.g., `**password**` and `**confirmPassword**`), use a **class-level** annotation.

**_Scenario: Ensure_** `**startDate**` **_is before_** `**endDate**` **_— annotation definition:_**

@Documented @Constraint(validatedBy = DateRangeValidator.class) @Target(ElementType.TYPE) // Applied at the class level @Retention(RetentionPolicy.RUNTIME) public @interface ValidDateRange { String message() default “Start date must be before end date.”; Class<?>[] groups() default {}; Class<? extends Payload>[] payload() default {}; }

**_Validator implementation:_**

import javax.validation.ConstraintValidator; import javax.validation.ConstraintValidatorContext; import java.time.LocalDate; public class DateRangeValidator implements ConstraintValidator<ValidDateRange, Event> { @Override public boolean isValid(Event event, ConstraintValidatorContext context) { if (event.getStartDate() == null || event.getEndDate() == null) { return true; // Let @NotNull handle null cases if needed } return event.getStartDate().isBefore(event.getEndDate()); } }

**_Usage in POJO:_**

@ValidDateRange public class Event { private LocalDate startDate; private LocalDate endDate;

// getters and setters } ```

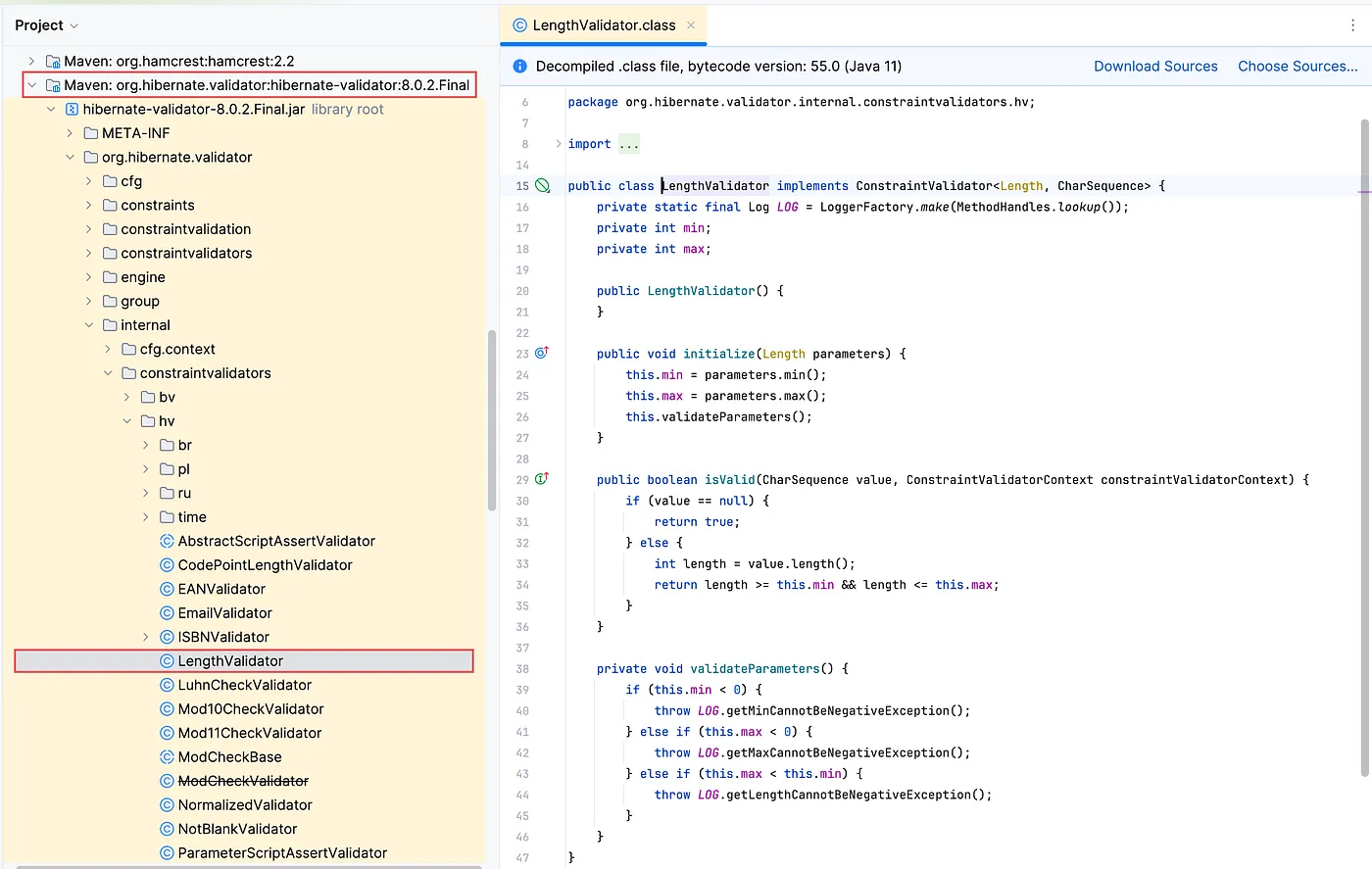

🟡 Understanding Bean Validation and Hibernate Validator Is Not That Hard

Bean Validation is the standard for validating object properties in Java, defining annotations like **@NotNull** and **@Size** but not enforcing them. Hibernate Validator is the default implementation, making these rules work and extending the API with custom constraints like **@Email** and **@CreditCardNumber**.

The spec is vendor-agnostic, so you can switch providers without changing code. In Spring Boot, Hibernate Validator is auto-configured when you add the **spring-boot-starter-validation** dependency, making it incredibly easy to get started.

🟡 You can replace Hibernate Validator in Spring Boot

Hibernate Validator is the default choice, but sometimes you might need an alternative due to performance, compatibility, or company preferences. Options include

- Apache BVal (lightweight but lacks features like @Email)

- Eclipse Jakarta Bean Validation (official but with fewer extras)

- or custom implementation (rarely practical).

Before switching, consider missing features, community support, and thorough testing to ensure validations still work as expected.

That’s a wrap! I hope you found this read as enjoyable as I did writing it — and maybe even picked up something new along the way.

As usual, stay tuned for more ✨